Can it be a good thing

when the number of women at an International Women’s Day march decreases by what could very well be half from the year before and many years before that? Usually, organizers are actively recruiting and hoping for more and more protesters every year. However, in a country that has one of the highest rates of violence against women in the world, could a decrease be a positive?

Mexico is one of those countries. In an article written in 2024, an estimated 10 women and girls were recorded as being murdered by an intimate partner or family member and, with only 1 in 10 victims daring to report, the real statistic is much higher. Moreover, with a 95% impunity rate, the number of predators convicted is as exceedingly low as the number of women and girls murdered is exceedingly high. Because of the extremity of machismo culture in Mexico, feminism only began to build as an organized and vocal movement in approximately 2014, originating in the Lesbian community. Until then, the majority of women were reluctant (or afraid) to speak out. It wasn’t until 2019, after a series of rapes and femicides that received national attention, that the women of Mexico had finally had enough of male violence and began to rise up en masse.

Besides the thousands of femicides that are reported and ignored by authorities or not reported at all, one femicide that received a lot of publicity—because of the ferocity with which her family fought for justice—was the 2017 murder of twenty-two-year-old university student Lesvy Berlin Rivera Osorio by her boyfriend on the campus of the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de México (UNAM). Lesvy’s body was found hung in a telephone booth; her boyfriend Jorge Luis Hernández González had hanged her to death with the telephone cord. As is usual in Mexico, her murder was catalogued and filed away as a suicide. The real case was closed. In order to buttress their victim-blaming tradition of suicide, the Public Prosecutors Office took to social media with accusations like “Osorio was an alcoholic and a drug user who was no longer studying at UNAM and had been living out of wedlock with her boyfriend.” Authorities insisted on investigating the victim’s sex life and family relations to build evidence of promiscuousness and mental instability that would back up their fabrication of suicide. More effort was put into making up evidence to discredit her case than investigate her murder.

Impunity reached a searing point in Mexico City

in the summer of 2019 when a series of assaults were committed by the police. In July and August, three women were raped by police officers; on July 10th, a 27-year-old homeless woman was raped by two other police officers; on August 3rd, a 17-year-old woman was gang-raped by four policemen in a police car; on August 8th, a minor was assaulted by a police officer in Museo Archivo de la Fotografía in México City. The women had had enough.

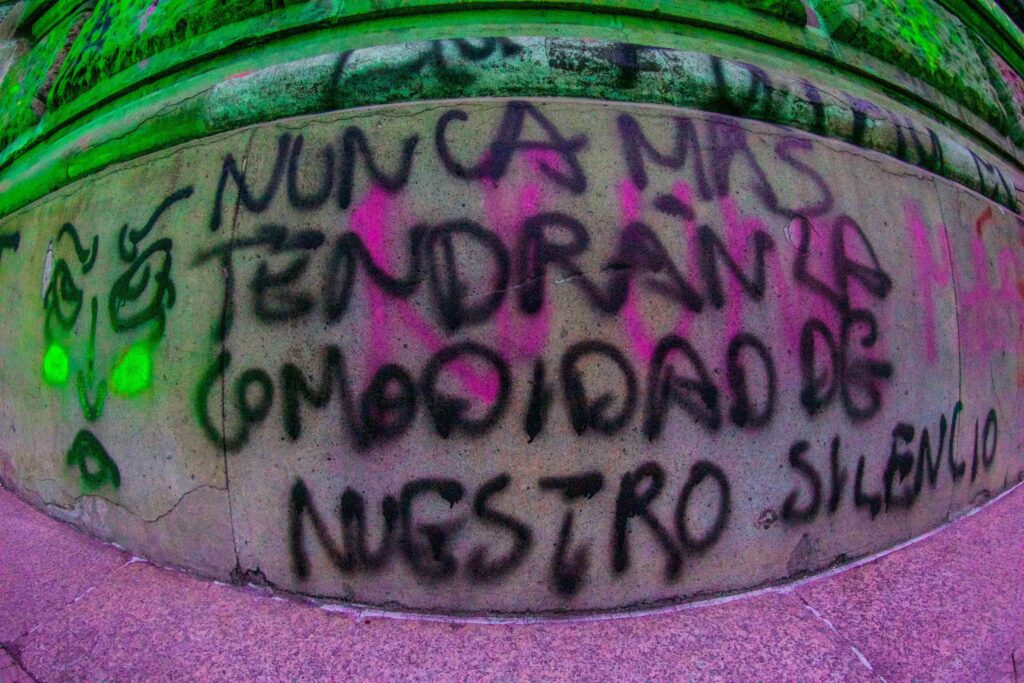

In direct response to the sexual violence committed by the police, women rose up on August 12th, 2019. This was the first time they expressed their rage publicly by starting the controversial act of writing on and defacing historical monuments (the first one being The Angel of Independence)—from which the women have since been criticized and their movement, to this day, discredited. Yet, regardless of the ridiculous accusations that the women are just as violent as the men who rape and murder them, what did they write on the base of Mexico City’s iconic Angel of Independence? “You are not going to have the comfort of our silence anymore.” And, with these words, the Feminist movement in Mexico had officially begun.

In a continued response to the impunity of the Mexico City police for the multiple rapes in the summer of 2019,

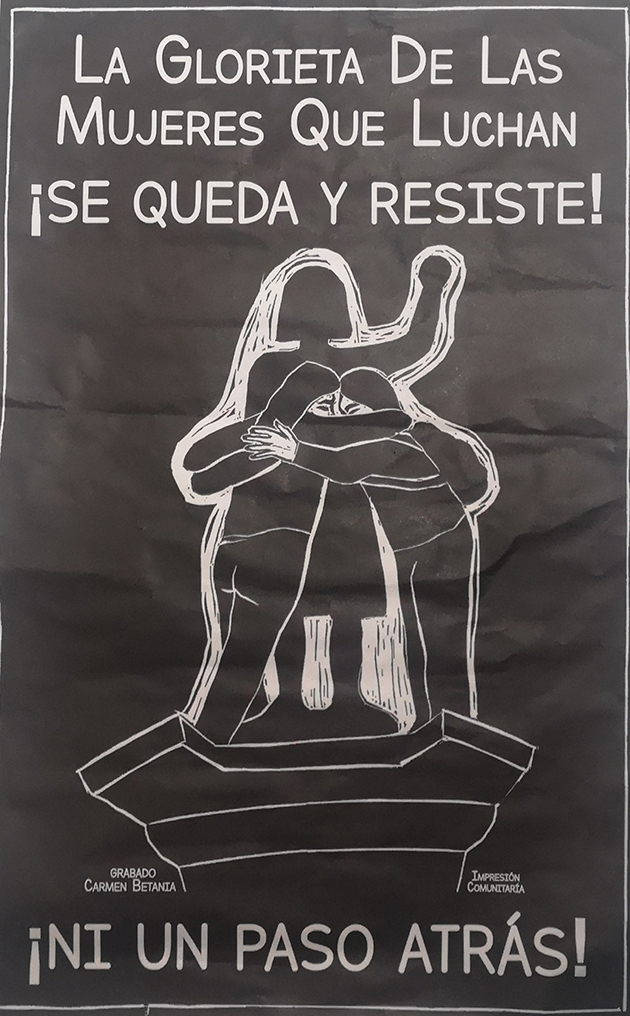

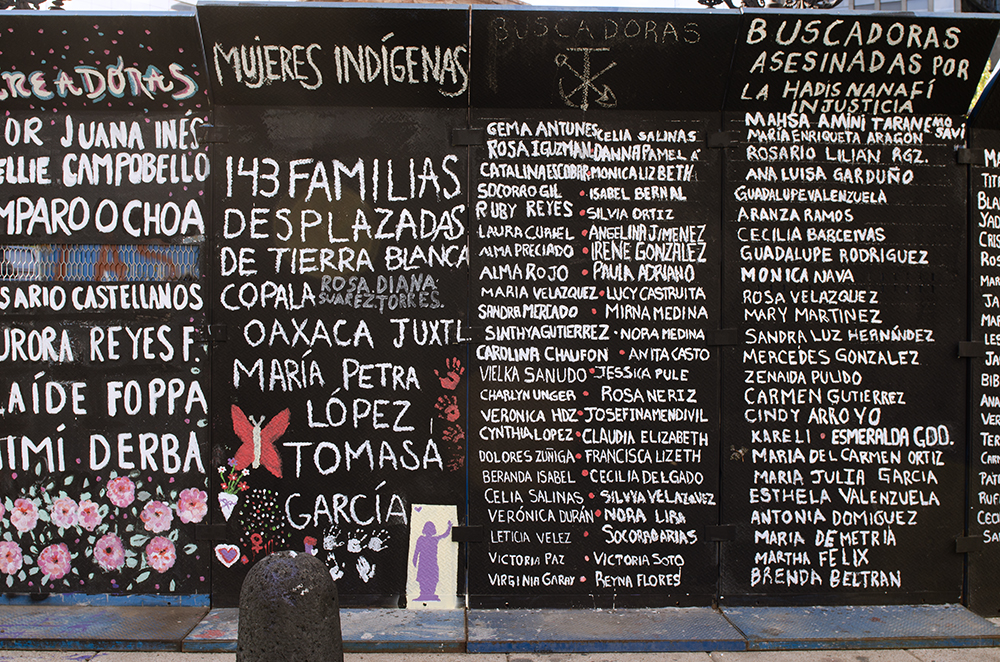

the women rose up again on November 25th, 2019 for the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women and the protests became increasingly vocal both in voice and act to the point where the city began covering the statues of the conquistadores (male colonizers) with saran wrap and surrounding the large monuments with corrugated metal to keep the women from covering these legacies of colonialism with such words as: Mexico Feminicidia! Basta Ya de Impunidad! (Enough Impunity Already, No Desaparecidas Ni Muertas, #NiUnaMenos (#NotOneLess), and plaster the walls with photos of unconvicted rapists and murderers. Saran wrap was gleefully torn off the monuments, climbed on and spray painted and the barriers torn down. The women were determined to be seen and heard.

On February 14th, 2020, there was a protest outside of President Obrador’s residence in the Zocalo—President Obrador, who did so much for the Mexican people initiating social programs and combating the Cartels from where they start with his Bullets Not Guns program and one of many legislations for justice, made a grave error when his response to women demanding more attention to be paid to the femicide epidemic discredited their cause as an act of the opposition. Then, on February 15th, 2020, seven-year-old girl Fátima Cecilia was found dead, her body wrapped in a plastic bag in a garbage can on a vacant lot. Fury escalated and the attendance of the Mexico City Women’s Day March from the Angel of Independence to the Zocalo began to surge: from 2020 to 2024 the march grew from 90,000 to 180,000.

I have been attending the Mexico City Women’s Day March (or 8M and it’s called here) since I moved here in 2015 and have watched it grow into one of the largest marches in the world. I was at the protest on November 25th, 2019. I remember tear gas, fires, the barricades kicked and then shoved down and gleefully jumped on to the cheers of onlookers and the hundreds if not a thousand police lining Reforma with their riot shields. I remember more tear gas. I remember when, after the city began to have only women police defending the monuments during women’s day, protesting women having fierce altercations with the women police officers accusing them of being traitors that often resulted in violence. I remember the year when the then mayor of Mexico City, now Presidenta Claudia Sheinbaum, gave all the women police officers flowers, and the controversy amongst the women protesters that ensued. I remember in 2020 when protective barricades were first put in place to protect the prioritized colonial monuments from vandalism. I remember the women climbing up and over those barricades and vandalizing the monuments of the conquistadores, nonetheless. I remember every surface along Reforma covered with revolutionary writing, and the irreverent pictures including photos of some of the 95% of rapists and murderers who received impunity plastered in every available space. And I remember on one of the 8M marches between 2020 and 2024 when I was walking back to Insurgentes and from the Zocalo at 5:30 to get my bike, the march we still happening. The women were still coming like a torrent 6 hours after the march had started.

But this year, 2025, was verging on the opposite.

Hundreds of thousands were expected; however, unlike last year when an official count of 180,000 was reported on March 10th, as of March 12th, no official count is available for this year. Maybe that is because it was so comparatively unsensational. My friend and I arrived at Insurgentes and Reforma at 2:30, an intersection where—based on the numbers over the last 5 years—the parade should have been crammed with women at that time. The boulevard was virtually empty. There were only a few women straggling around or sitting on the side as confused as I was. There was little to no writing on the walls; barely any of the buildings had been boarded up. We couldn’t even hear drums and chants. There were definitely no helicopters thumping ominously over head or drones with their swat-deserving buzzing above. Yes, a few of the conquistadors’ statues had been painted green and purple and playfully blasphemed by green scarves with the women’s symbol and purple flowers perched on their heads. But that was about it.“Where is the march? Where is everyone?” I asked a row of women, their placards leaning against a wall on the side of the broad boulevard.

“They’re up there. They passed about half an hour ago.”

“Do you know why?”

“No,” they responded. “We don’t understand either.”

My friend and I walked for about 15 minutes and finally reached the march.

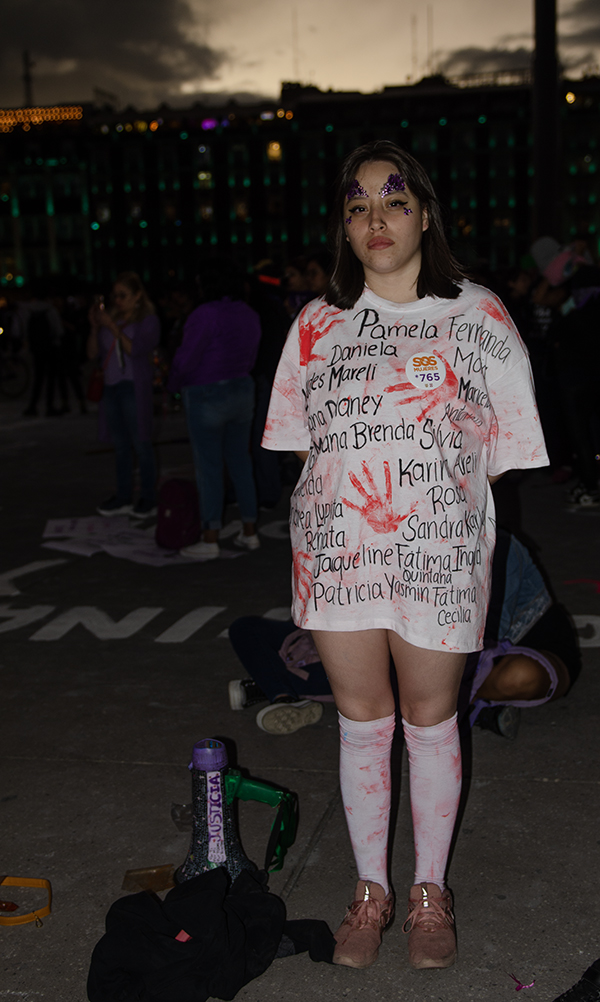

There were the usual triumphant chants, and the on-cue jumping that the young women do in time with their chant about snubbing their noses at machos, a cumbia marching band with dancers and hoola-hoops; there was a 2-women feminist punk band blaring irreverence with their electric guitars followed by a feminist ukelele group strumming and the placards with the powerful proclamations for justice that Mexican women pride themselves in. There were a few walls plastered with the faces of rapists. Feminist graffiti became more visible. A few of the infamous militants clad entirely in black, balaclavaed and armed with spray paint climbed on top of bus shelters to write: #creaenella (believe her). A large sign to give justice to Fatima was help up by women who had climbed up onto the sides of a monument. But, after 3 hours, I only saw 3 women police officers. I didn’t have to get through a wall of police with their riot shields when I wanted to run farther up to get photos of the march from different perspectives. There was levity, bereft of the abundance of drawn, traumatized faces. It was different. It was more like a Woman’s Day march in Canada, in a first-world country—albeit with Mexican frivolity and flavour. It was more a celebration of women rather than the funeral marches ignited by guerilla warfare of years past.

I’m not saying the Mexico City 8M wasn’t powerful this year

and women were not speaking out passionately against the continued reality of extreme gender-based violence in Mexico and the impunity for male perpetrators. I am wondering what it means when a march that was enormous and one of the biggest in the world was so much smaller; I am curious as to why there was less overt anger and retaliatory vandalism and what that means and whether a decrease in the number of women at an International Women’s Day march could be a mark of improvement in the lives of women in a country that has been scourged with gender violence for decades, if not centuries. Yes, there are still some reports that nothing has changed and that the 25% decrease in homicides in Mexico with the new administration of Presidenta Claudia Sheinbaum has affected nothing. Yet, with the numbers at an all-time high on 8M 2024 and this year’s march—even held on a Saturday when most people don’t work—so much smaller, how can one explain this very obvious decrease? How can one explain the subdued anger? The tempered ferocity, the lack of police corresponding to the lack for the need for police enforcement? With national day care, assistance for single mothers, abortion now available to women nationally and the other social programs implemented by Obrador that could be decreasing the immasculanization and anger of men—which is so often the cause of violence against women—being continued by Sheinbaum and the decrease in homicides be making a real difference in the lives of women in Mexico? Could it be logic that when a people are better off, violence lessens in general and, thereby, decreases the rates of femicide and rape? It’s hard to say in a country where the conservative opposition will do anything to undermine a socialist government. However, in the meantime, we can only hope that the decrease in numbers at Mexico City’s Women’s Day March 2025 is a sign that violence really has lessened in Mexico—for women and men.

Yours,

The Logical Feminist.

For a more extensive look at the birth of the Mexican feminist movement, see my 2020 article:

“The Life of a Woman is More Important than an Historical Monument.”

For an analysis of violence perpetrated against Mexican men, see this article on a solution:

“Justice Begins with the One Beside You: The Revolution of Nacidos Para Triunfar.”

For an analysis of the President Andrés Manuel López Obrador administration’s (2018-2024) strategy to end violence where it starts, see Part One of my article on the Morena Revolution:

“And this is a Good Thing: Contextualizing the 2024 Mexico Election. Part One.”